A collaboration between UXSEA and Studio Dojo, this article seeks to better understand the experiences of Imposter Syndrome within the UXSEA community. To gather directly data from UX-ers , a survey was sent out to the various UX communities within the Southeast Asia region. This article serves as a commentary of the patterns observed from the survey data, rather than a detailed quantitative analysis of it.

Imposter Syndrome (IS) is understood as an internal sense of feeling like a fraud. You fear that you will be discovered as incompetent at your job and you question how you got a seat at the table. You attribute your achievements to factors other than your own abilities.

With IS being a new buzzword, especially in pop-psychology, it is not hard to find resources regarding it.

A simple Google and Youtube search on it would result in many TEDTalk videos and articles related to it.

As one consumes these resources, a pattern emerges on how the dominant discourse of IS seems to be:

“IS is something that is commonly experienced by many, in fact up to 70% of us.”

“IS can be overcome.”

“Here’s a list of actions you can take to fix yourself and be better.”

However, there is a seeming incongruence between the individual-focused solutions and the fact that IS is an experienced faced by many. If IS is truly a common experience, why then are we focusing the conversation solely on individuals to take actions? Could there perhaps be a larger, and systemic, reason that is contributing to this phenomenon faced by many?

Over the past decade, more conversations regarding commonly experienced phenomenons, such as increase in mental illness cases, have shifted from being individual-focused to a societal-focused one. With the shift creating a more whole understanding of the phenomenons, these discourses have benefitted by involving the whole society to be responsible for the solutions. Could IS perhaps benefit from the same shift?

With this tangent in mind, this article explores the presence of IS within our UXSEA community. Is IS truly a common experience? And if so, what factors are causing this phenomenon?

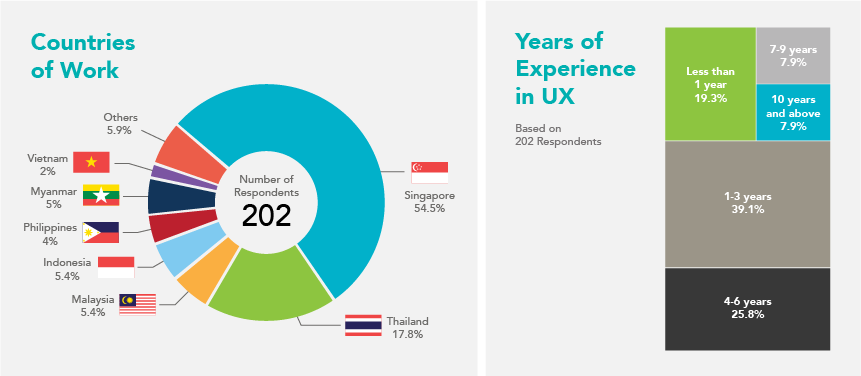

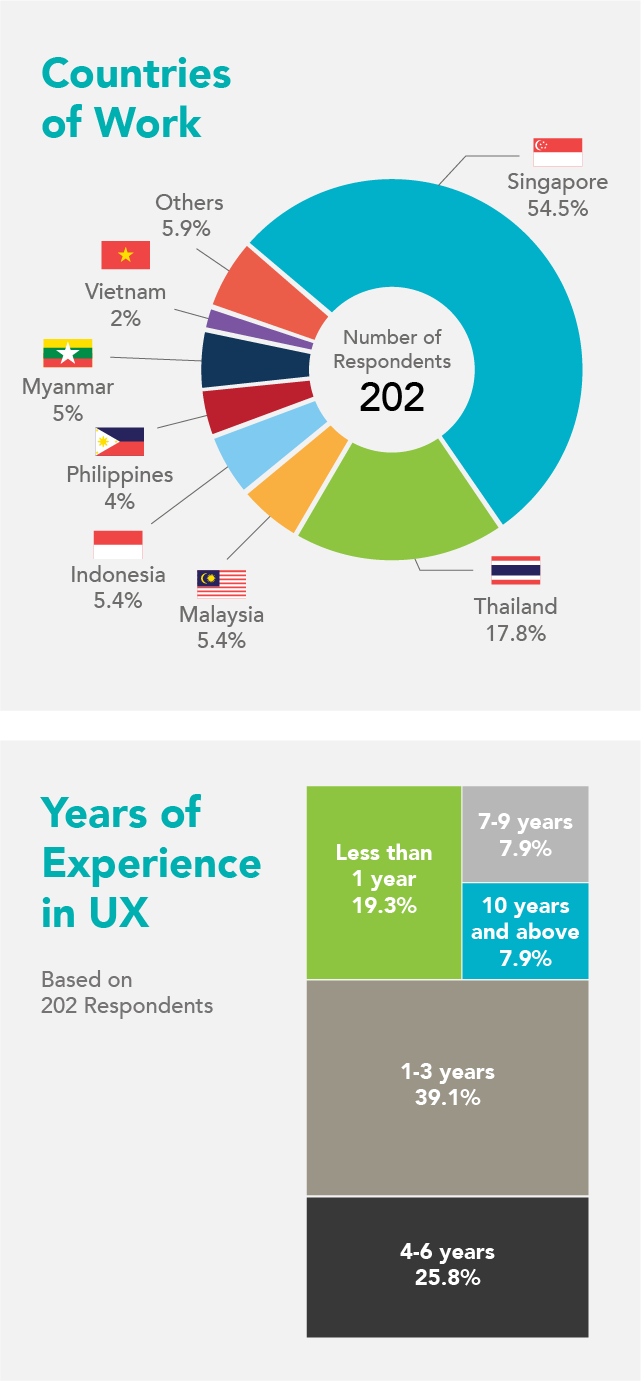

To better understand the IS experiences within the UXSEA community, a survey was sent out to various UX communities in Southeast Asia. Questions mostly centred on whether they identify with having IS, factors that they think have contributed to it, and kinds of support they would want in navigating it. 202 responses from different countries later, here are some thoughts and perhaps more questions that arose.

A common experience, regardless of nationality

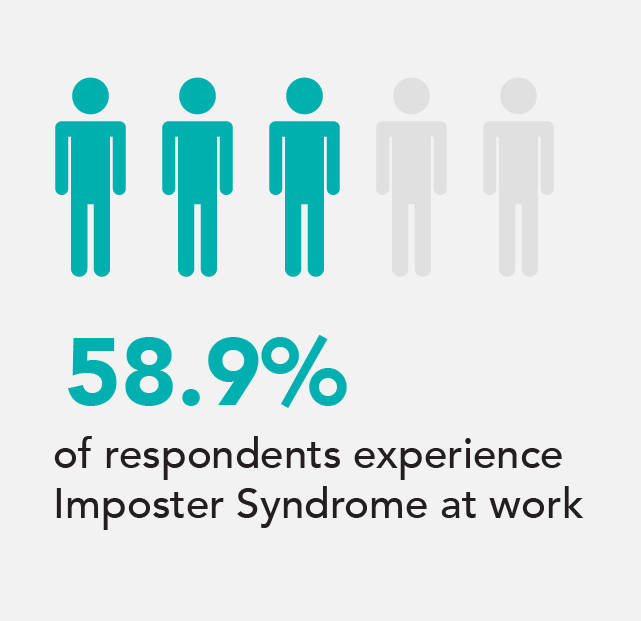

Well, the answer is Yes.

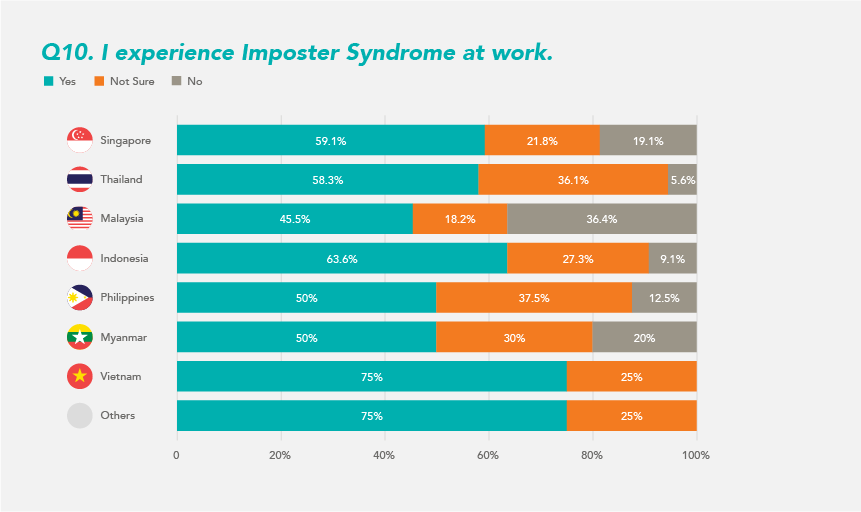

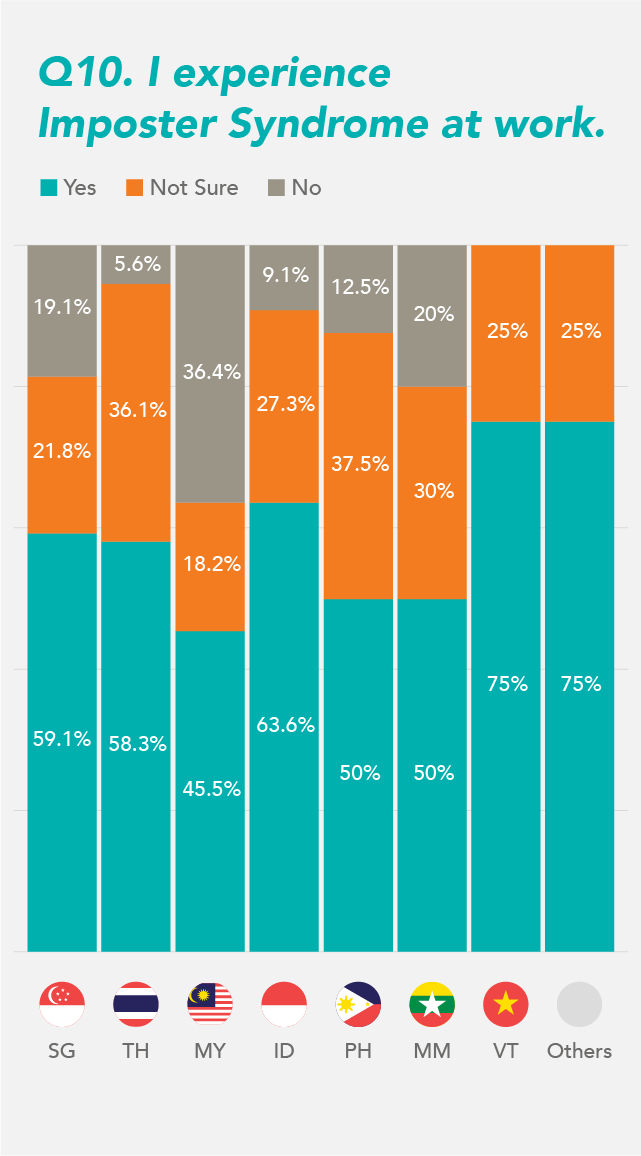

About 60% of the respondents express that they do experience IS at work. This largely parallels a study that shows that more than 70% of people will experience IS once in their life.

What makes this more interesting is observing the same trend across all eight countries. Within each country, the ‘Yes’ group is the largest, followed by ‘Not Sure’, and then ‘No’.

Thus, the high level of IS can be seen as a regional phenomenon, rather than being country-specific.

This suggests that the different country-related factors – be it their national culture or maturity of the UX industry – may be not be as critical in making one incline to experience IS.

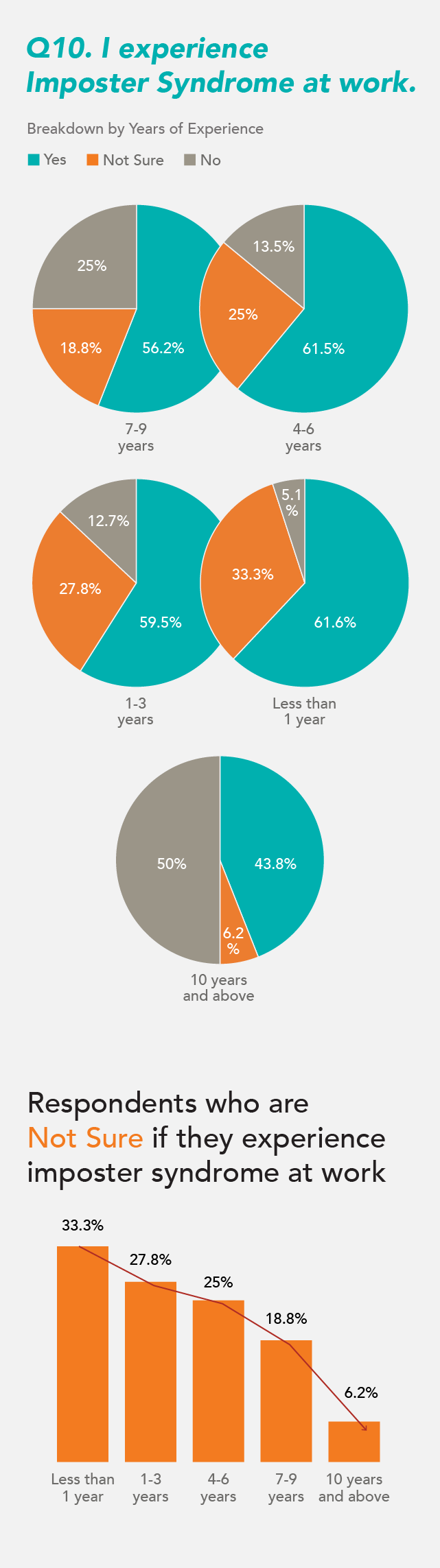

Well then, what about one’s seniority? Would a UX practitioner that has worked longer in the industry be less likely to have IS?

Seniority doesn’t guarantee lesser likelihood of IS.

There is no guarantee that more senior practitioners will not experience IS. While the survey results show that as seniority increases, the percentage of ‘Yes’ group generally decreases, this is counter-balanced by the fact that within each seniority group, the ‘Yes’ group forms the largest percentage. This is heightened by the finding that even amongst practitioners who have worked in the industry for more than 10 years, half of them may still experience IS.

This is significant as it shows how IS is present at all seniority levels and problematises the popular myth that IS disappears over time and experience. While there is no guarantee that time reduces likelihood of IS, what is clear is that the longer one works in UX, the clearer he is on whether he is experiencing IS or not. This is seen in the decrease of ‘Not Sure’ as seniority increases.

So, if the country and seniority do not significantly influence IS, what factors are causing it then?

Top 5 significant contributing factors

Respondents were presented a list of possible factors and asked to highlight those that contributed to their experience

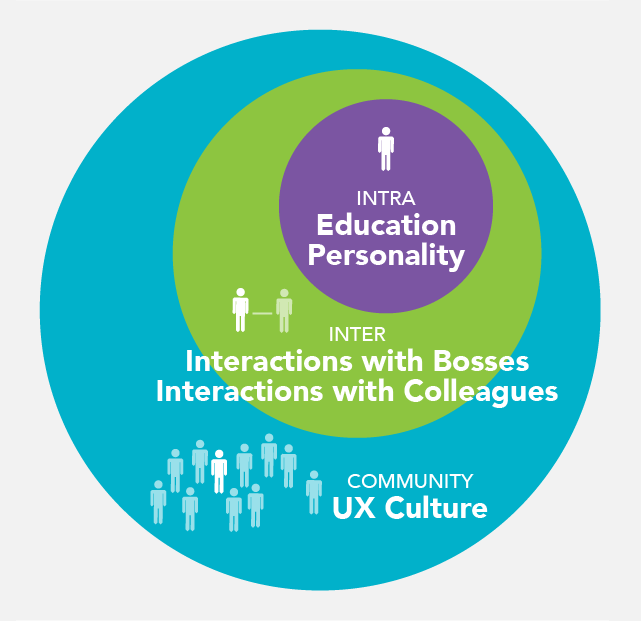

of IS. The top five chosen by UX practitioners are

- UX Culture

- Education background

- Personality

- Interactions with Bosses

- Interaction with Colleagues

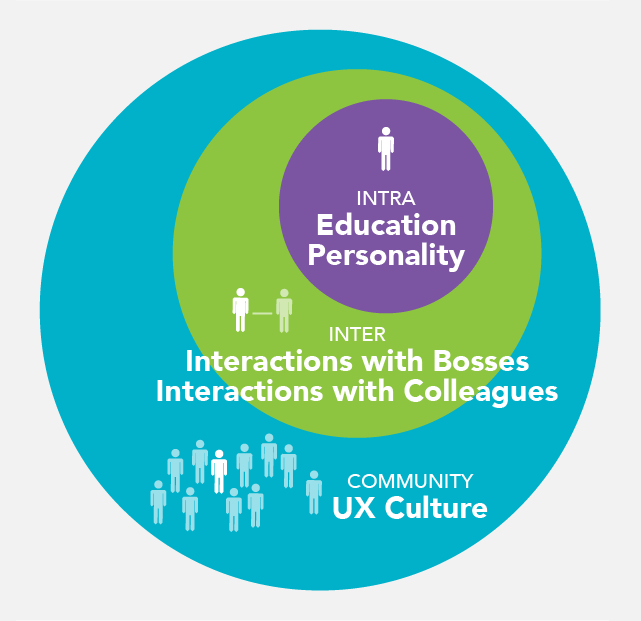

Between the five factors, there’s a mix in terms of level of interactions/relationship with others. While Education and Personality relate more to the intrapersonal aspects of

the person, Interactions with Bosses and Interaction with Colleagues show the interpersonal relationships they have with other individuals. Lastly, UX culture indicate the UX practitioner’s relationship with the community that they deem to be apart of.

Given the mix in levels of interaction, it highlights that the experience of IS goes beyond just the individual himself. It arises also because of the interactions he has with those around him (i.e. his bosses and colleagues) as well as with the culture that he is entrenched within because of the UX work he does.

If our experiences of IS is a complex product of all these different factors, perhaps then a sustainable solution to IS should befittingly also go beyond the individual and address the different factors?

What does competency look like in UX?

Underlying IS is a sense that you do not comfortably belong to whichever group you are part of. You worry that you will get caught by your work team for not being as competent as they assume and expect you to be. Among the respondents who experience IS, 78% agree with constantly having that worry. This raises the question – what does ‘competency’ look like in UX?

As the respondents elaborate on instances of feeling IS and how those five above-mentioned factors contribute to them, it became clear how they were commonly understanding competency to be.

To them, a competent person in UX has the characteristics below:

Visible

- “they’re well-known”

- “always showcasing their successes”

- “has a cult following”

Formally design-educated

- “has a degree or masters in UX”

- “taught properly/formally on UX methods,

- didn’t learn by trial-and-error”

Has showmanship

- “extroverted, confident personalities”

- “charismatic and great presenters

- even if not backed up by technical skills”

Articulate in UX knowledge

- “confident to teach juniors”

- “able to answer clients’ questions”

- “quick in giving effective feedback”

‘Breathes’ UX

- “always keeping up with UX events and classes”

- “did their due and didn’t take shortcuts like

- UX bootcamp”

In seeing how UX practitioners understand competency to be, it became clear that these are the same set of criteria that they are expecting of themselves when assessing how competent they are in their jobs. The worry of not meeting their job expectations possibly lies in the worry of not meeting these criteria that have been internalised.

While these criteria are arguably self-imposed, it is critical to acknowledge that these criteria are also learnt by observing their surroundings and noticing the kinds of competencies that are being recognised and celebrated within the UX community.

So, what now?

When asked for solutions that may address their IS, here are five common ones suggested by our respondents.

- Build our own self-confidence

- Accept IS as part of our learning journey

- Create a safe workplace where we can learn and make mistakes

- Establish clearer evaluations at work so that we can assess our own abilities

- Cultivate a UX culture of care & openness so that we can openly ask questions, learn from others, and share the setbacks we have experienced

Similarly, what’s interesting is how the suggested solutions themselves involve the different layers within the UX community. While some solutions are aimed at individuals to make the effort to better themselves, others are targeted at the workplaces and larger UX community to consider and make the effort to create necessary changes. A complex problem requires a complex and layered solution.

Imposter Syndrome is not solely an individual problem, it is also a social one.

Having heard from the UXSEA community, perhaps one can seek comfort in acknowledging the following: Many UX practitioners are experiencing IS. There is a multitude of reasons that contribute to it but what seems important to realise is that it goes beyond individuals. Workplaces may also contribute to it, and so does the larger UX culture that they are a part of.

In the same breath, perhaps one too can be more aware that by being part of the community, they may be contributing to the IS experience of another person, be it their peers or those who report to them. It’s worthwhile then to question how the community can collectively create an environment that better manages IS.

Here are some great resources to begin our conversations with Imposter Syndrome:

- https://hbr.org/2021/07/end-imposter-syndrome-in-your-workplace

- https://thesociologicalreview.org/collections/private-troubles-public-issues/imposter-syndrome-as-a-public-feeling/

If you like this article, do check out our other articles at www.studiodojo.com/blog/